The Tombstone Epitaph

The Tombstone Epitaph is a historic newspaper in the American West, closely tied to the lore of the Wild West and the famous town of Tombstone, Arizona. It was founded on May 1, 1880, by John Clum, a former Indian agent and the first mayor of Tombstone. The newspaper played a significant role in documenting the events of one of the most storied periods in American history.

Founding and Early History

John Clum founded the Tombstone Epitaph during a time when Tombstone was booming due to the discovery of silver in the nearby mountains. The town quickly grew into one of the largest and most notorious in the West, attracting miners, gamblers, outlaws, and lawmen alike. Clum, a staunch Republican and supporter of law and order, used the paper to promote his views and to support the efforts of the Earps, who were the town’s law enforcement at the time.

The newspaper’s name, “Epitaph,” was reportedly chosen by Clum as a nod to the violent and often deadly nature of life in Tombstone. He believed that the paper would serve as the “epitaph” for many of the stories and lives that would pass through the town. The Epitaph became known for its bold headlines, sensational stories, and fierce editorials.

The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

One of the most famous events covered by the Tombstone Epitaph was the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral on October 26, 1881. The shootout between the Earp brothers—Wyatt, Virgil, and Morgan—and Doc Holliday on one side, and the Clanton and McLaury brothers on the other, was a pivotal moment in Tombstone’s history. The newspaper provided a detailed account of the event, and its coverage helped shape the public’s perception of the Earps as lawmen battling against lawlessness.

Decline and Revival

As Tombstone’s silver mines began to decline in the late 1880s, the town’s population dwindled, and the Tombstone Epitaph faced financial difficulties. The paper struggled to survive but managed to continue publishing, albeit with less frequency. Over the years, the Epitaph shifted from being a daily to a weekly, and eventually to a monthly publication.

In the 20th century, the Tombstone Epitaph experienced a revival as interest in the Old West and its colorful history grew. The newspaper became a cherished piece of Americana, and its archives were preserved as valuable historical records. In the 1960s, the paper was revived as a historical publication, focusing on the history of Tombstone and the American West. It continues to be published today, both as a historical monthly and as a tourist newspaper, providing visitors with stories and insights into the town’s storied past.

Legacy

The Tombstone Epitaph remains one of the most iconic newspapers of the American West. Its coverage of the events in Tombstone, particularly during the 1880s, has made it a key source for historians and enthusiasts of the Wild West. The newspaper not only documented the events of a bygone era but also helped shape the legends that continue to captivate people today.

Tombstone Epitaph Headlines

The Tombstone Epitaph – March 27, 1882Frank Stilwell On March 27, 1882, The newspaper the Tombstone Epitaph announced the murder of Frank Stilwell in Tucson Arizona. Frank Stilwell was an outlaw… |

The Tombstone Epitaph, March 20, 1882The Tombstone Epitaph, March 20, 1882 reports of the murder of Tombstone Resident Morgan Earp while playing pool in Tombstone, Arizona. This event followed the… |

The Tombstone Epitaph, October 27, 1881The following is the original transcript of The Tombstone Epitaph published on October 27, 1881 on the infamous gun fight at the O K Corral… |

Camp Osito Road – 2N17

Camp Osito Road is a back country 4×4 trail which connects Knickerbocker Road to Skyline Drive in Big Bear, California. The seldom travelled road is an access route to a local Girl Scout Camp.

Route 2N17 branches from the Knickerbocker trail about two miles from either end and wanders towards the west by Camp Osito. From there, the route continues through the heart of the San Bernardino Mountains until it intersects with Skyline Drive. This is at best an intermediate trail and offers views of Big Bear Lake and the surrounding forests and manzanita groves.

Big Bear Mountains, nestled in the heart of Southern California, offer a breathtaking escape into nature’s splendor. With a majestic backdrop of towering pines and rugged terrain, this mountainous haven beckons outdoor enthusiasts and adventure seekers alike. The towering peaks, including San Gorgonio Mountain, provide year-round recreational opportunities, from exhilarating ski slopes in the winter to invigorating hiking trails during warmer months.

Due to the proximity to Big Bear, it is quite common for this route to be used by hikers, bickers, quad riders and 4x4s alike, so keep an eye out for traffic.

Trail Summary

| Name | Camp Osito Road |

| Location | Big Bear, San Bernardino, California |

| Latitude, Longitude | 34.2243, -116.9378 |

| Elevation | 7,500 feet |

| Distance | 1.8 Miles |

| Elevation Gain | 352 feet |

Trail Map

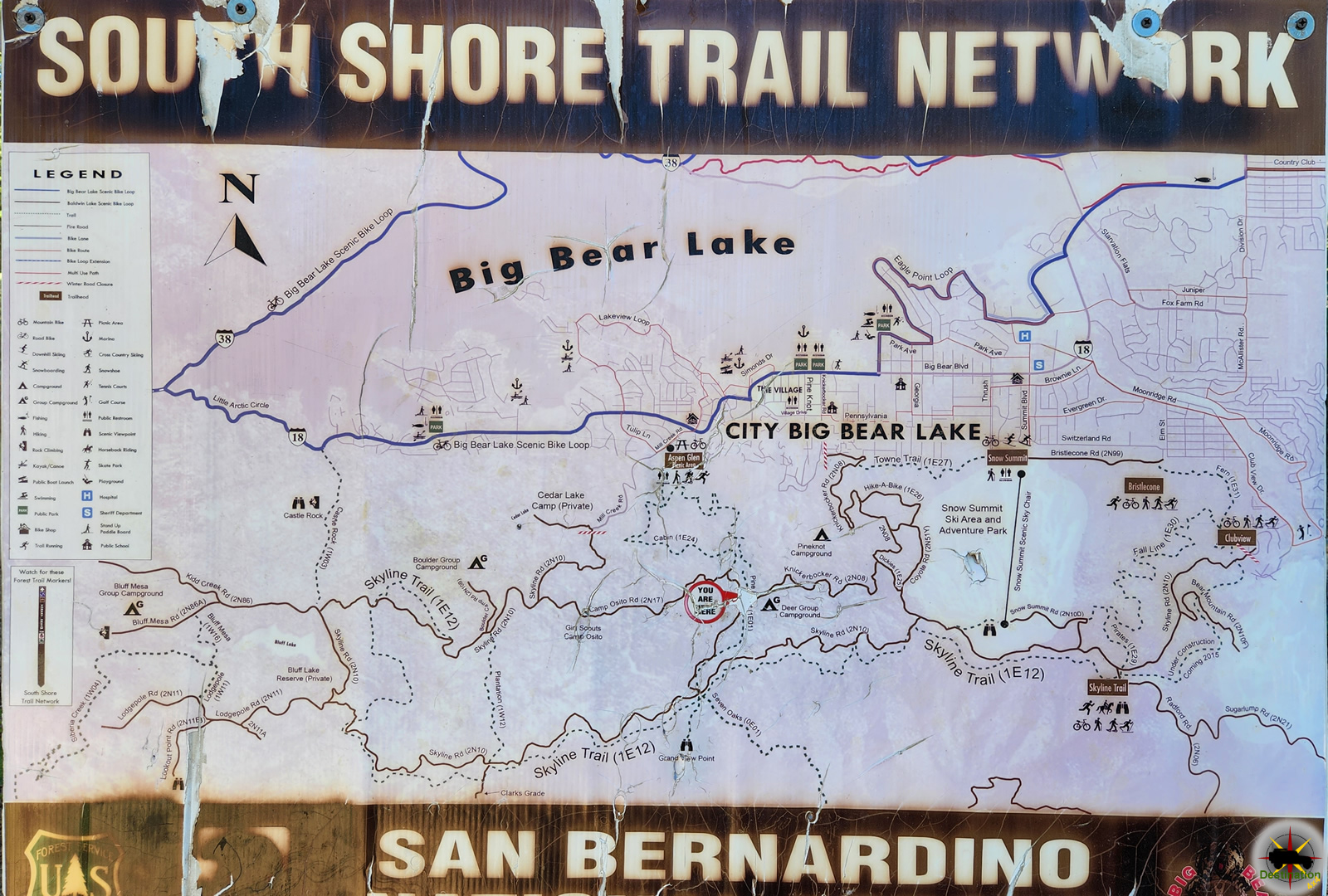

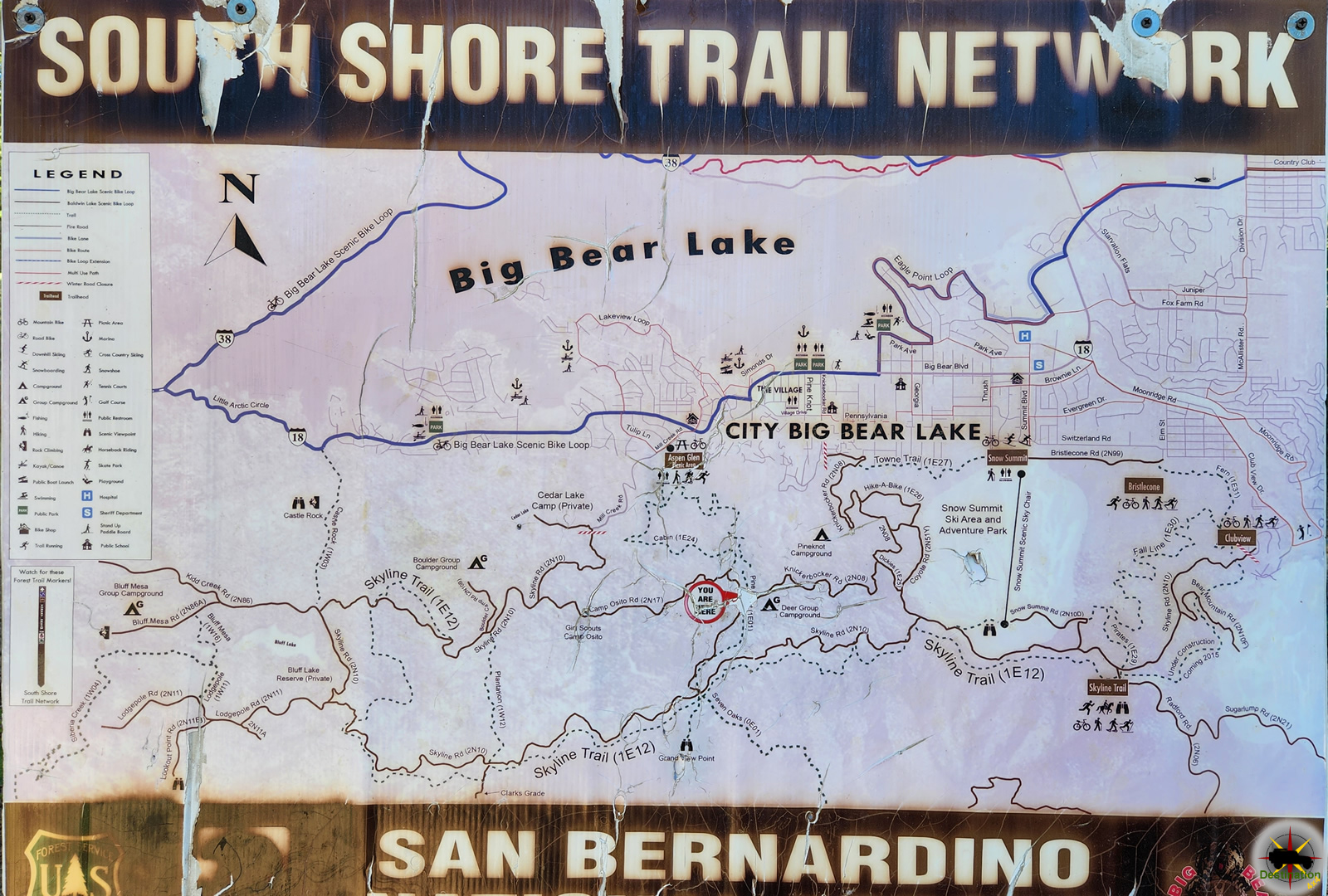

Camp Osito Road is part of the South Shore Trail Network located in the San Bernardino Mountains, near Big Bear, California.

Camp Osito Road – 2N17Camp Osito Road is a back country 4x4 trail which connects Knickerbocker Road to Skyline Drive in Big Bear, California. The seldom travelled road is… |

Clarks Grade 1N54Clarks Grade 1N54 Trail Head dropping down into Barton Flats from Skyline Drive. Clarks Grade 1N54 is a steep and scenic descent from the top… |

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08Knickerbocker Road - 2N08 is a steep and beautiful drive from near the town of Big Bear, California to Skyline Drive. The route is a… |

Skyline Drive 2N10Skyline Drive 2N10 offers higher elevation views of Big Bear, California Skyline Drive 2N10 is the unofficial name for USFS Road 2N10 that begins just… |

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08 is a steep and beautiful drive from near the town of Big Bear, California to Skyline Drive. The route is a popular destination and common for hikers, bikes and vehicles alike. The route winds up the mountain from the village in Big Bear up to the top of the mountain offering some spectacular vistas and the valley below.

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08 is accessed from Highway 18 in Big Bear, about two blocks east of the village. The trail head is located 3/4 of a mile from the highway off of Knickerbocker Road. The trail begins with a tight left turn and steeply gains alititude. from the valley floor on its journey up to Skyline Drive.

Along the route, you journey deep into a lush pine forest with a few seasonal streams to nourish the lush green plant life. Manzanita Bushes fill the landscape, along with a variety of seasonal wild flowers as you continue to climb to the ridge of the mountain. Don’t forget to admire the views of Big Bear lake as you make the journey.

Once the trail terminates at the Grand View Vista at Skyline drive, there is a very small parking area to relax, picnic and enjoy the alpine view of Barton Flats and valley below. From here, you can return as you came, or pick any of several trails from the South Shore Trail Network including Skyline Drive,

Knickerbocker Road Trail Summary

| Name | Knickerbocker Road – 2N08 |

| Location | Big Bear, San Bernardino County, California |

| Latitude, Longitude | 34.2162, -116.9192 |

| Length | 4 Miles |

| Elevation Gain | 890 feet |

Trail Map

Knickenbocker Road is part of the South Shore Trail Network.

Camp Osito Road – 2N17Camp Osito Road is a back country 4x4 trail which connects Knickerbocker Road to Skyline Drive in Big Bear, California. The seldom travelled road is… |

Clarks Grade 1N54Clarks Grade 1N54 Trail Head dropping down into Barton Flats from Skyline Drive. Clarks Grade 1N54 is a steep and scenic descent from the top… |

Knickerbocker Road – 2N08Knickerbocker Road - 2N08 is a steep and beautiful drive from near the town of Big Bear, California to Skyline Drive. The route is a… |

Skyline Drive 2N10Skyline Drive 2N10 offers higher elevation views of Big Bear, California Skyline Drive 2N10 is the unofficial name for USFS Road 2N10 that begins just… |

Chloride Arizona

Chloride Arizona is the oldest continuously inhabited Silver Mining town located in Mohave County, Arizona. The name derives its named from Silver Chloride (AgCl) which is found in abundance in the local Cerbet mountains.

Chloride’s modern history began in the late 19th century when prospectors, drawn by rumors of silver and other valuable minerals, began to explore the nearby hills and canyons. In 1863, a prospector named John Moss struck silver in the area, leading to a flurry of activity as more miners and settlers arrived. The first official post office was established in 1866, and Chloride was officially born.

Chloride experienced rapid growth during the late 1800s as mines produced substantial amounts of silver, lead, zinc, and other valuable minerals. The town’s population swelled. Businesses, saloons, and other establishments sprung up to cater to the needs of the growing community. At its peak, Chloride boasted a theater, several hotels, and a bustling main street.

However, like many mining towns of the era, Chloride’s prosperity was short-lived. Fluctuating metal prices, mine closures, and the depletion of easily accessible minerals led to a decline in the town’s fortunes. By the early 20th century, Chloride entered a period of decline. Much of its population began to dwindle as residents sought opportunities elsewhere.

Despite the challenges, some residents remained in Chloride, and the town managed to maintain a semblance of its former self. The 20th century saw the rise of tourism as visitors were drawn to Chloride’s picturesque desert landscapes, historical buildings, and remnants of its mining heritage. Efforts to preserve the town’s history led to the restoration of several historic structures, including the Monte Cristo Saloon. The saloon proudly claims to be Arizona’s oldest continuously operating bar.

Modern Relevance

In recent decades, Chloride has experienced a revival fueled by a mix of nostalgia, artistic expression, and a desire to escape the hustle and bustle of city life. The town has attracted a diverse group of residents, including artists, retirees, and those seeking a slower pace of life.

One of Chloride’s most unique and captivating features is the open-air Chloride Murals project. In the early 1960s by local artist Roy Purcell, this project has transformed the town into a vibrant canvas. Murals depicting scenes from Chloride’s history, Native American culture, and the American West decorate the sides of buildings and rock formations.

Chloride Arizona Town Summary

| Name | Chloride, Arizona |

| Location | Mohave County, Arizona |

| Latitude, Longitude | 35.4047, -114.1812 |

| Elevation | 4,022 ft (1,226 m) |

| GNIS | 2882 |

| Population | 229 |

| Max Population | 2000 |

Trail Map

References

Warm Springs Canyon Road

Warm Springs Canyon Road is a rugged, scenic backcountry route in the Panamint Range of Death Valley National Park, California, offering a challenging off-road adventure through stark desert landscapes, historic mining sites, and access to the tranquil Warm Springs Camp. This unpaved road is not a hiking trail but a 4×4-only route, winding through the heart of the Panamint Mountains from Panamint Valley to Butte Valley. Spanning approximately 17-20 miles one-way with elevations from 1,500 to over 4,000 feet, it features dramatic canyon walls, Joshua tree-dotted flats, and occasional wildlife like bighorn sheep or wild burros. As of August 14, 2025, the road is open following repairs from the August 2023 flash floods caused by Hurricane Hilary, but conditions remain rough with loose gravel, rocky sections, and potential washouts during monsoon season (July-September). Always check the National Park Service (NPS) website or visitor centers for real-time road status, as extreme heat (summer highs often exceed 110°F) and remoteness require meticulous preparation.

Route Description and Access

- Starting Point: The road begins near the ghost town of Ballarat in Panamint Valley, accessible via paved roads from Trona or Highway 178. A sign marks the turnoff from Panamint Valley Road onto the graded dirt of Warm Springs Canyon Road, entering Death Valley National Park after a few miles.

- Length and Elevation: Approximately 17-20 miles one-way to Butte Valley, with an elevation gain of about 2,500 feet. The first 10-12 miles to Warm Springs Camp are relatively manageable, while the final stretch to Butte Valley includes steeper, rockier terrain.

- Primary Route: From Ballarat, the road heads east through Warm Springs Canyon, passing abandoned talc mines and climbing through narrow, rocky washes to Warm Springs Camp (mile 10-12). It then continues to Anvil Spring and Striped Butte in Butte Valley.

- Alternative Routes: A southern spur from West Side Road (25 miles south of Furnace Creek) joins the main route near Warm Springs Camp but is rougher and less direct. For experienced drivers, the road can extend over Mengel Pass (extremely rugged, with boulder fields) to Goler Wash and Barker Ranch, though this requires advanced 4WD skills.

- Travel Time: 2-4 hours one-way, depending on vehicle speed, road conditions, and stops for photography or exploration.

Difficulty and Vehicle Requirements

- Difficulty: Moderate to difficult for off-roading. The initial 8-10 miles to Warm Springs Camp require high-clearance vehicles due to loose gravel, washouts, and occasional boulders. Beyond the camp, 4WD with low-range gearing is mandatory for steep grades and rocky sections, especially toward Butte Valley or Mengel Pass.

- Vehicle Requirements: High-clearance 4×4 vehicles with all-terrain tires are essential. Standard cars or low-clearance SUVs are unsuitable and risk damage or stranding. Carry a full-size spare tire, recovery gear (shovel, traction mats), and air-down tires for better traction. Novice drivers should avoid solo trips due to the remote setting and lack of cell service.

- Safety Note: Recovery services are expensive and may take hours to reach you. Carry extra fuel (nearest gas is 50+ miles away in Furnace Creek or Trona), water (1 gallon per person per day), and a satellite phone or communicator, as cell coverage is nonexistent.

Current Conditions (August 2025)

- Road Status: Reopened in December 2023 after significant flood damage from Hurricane Hilary in August 2023. Recent reports confirm passability for properly equipped 4×4 vehicles, though sections remain washboarded, rocky, and prone to erosion. Monsoon season (July-September) increases flash flood risks, potentially causing temporary closures. No snow concerns in summer, but extreme heat poses a danger—travel early morning or late afternoon.

- Weather Considerations: Daytime temperatures often exceed 110°F in summer, dropping to 80-90°F at night. Spring and fall offer milder conditions (60-80°F), with occasional wildflower blooms. Winter may bring light snow at higher elevations.

- NPS Alerts: Check www.nps.gov/deva for real-time updates, as flash floods or heavy rains can alter road conditions rapidly.

Trail Map

Points of Interest

- Warm Springs Camp: Located 10-12 miles from the start, this oasis features natural hot springs feeding concrete pools (around 100°F), shaded by palm trees. It’s a primitive campsite with pit toilets but no potable water—bring your own or treat spring water. A perfect spot for a break or overnight camping.

- Talc Mines: Abandoned mining sites, including the Pfizer and Western Talc operations, dot the canyon with rusted equipment and structures. Explore on foot but avoid entering unstable shafts or removing artifacts.

- Geological Features: The canyon showcases colorful rock layers, from volcanic tuff to metamorphic formations, with sparse vegetation like Joshua trees and creosote bushes.

- Butte Valley Access: The road’s endpoint in Butte Valley offers access to Striped Butte (a colorful, 4,744-foot peak), the Geologist’s Cabin (a historic stone structure), and Stella’s Cabin at Greater View Spring.

- Wildlife: Look for wild burros near the springs, bighorn sheep on rocky slopes, or desert tortoises in spring. Avoid disturbing wildlife and maintain distance.

Tips for Visitors

- Permits: Free backcountry camping permits are required for overnight stays, available at Furnace Creek Visitor Center or online at www.nps.gov/deva. Day use requires no permit but a park entrance pass.

- Safety Essentials: Bring ample water, food, first-aid kit, maps, and emergency supplies. Inform someone of your itinerary and expected return. Carry a satellite communicator for emergencies, as the nearest help is in Furnace Creek (50+ miles).

- Best Time to Visit: October through April for cooler temperatures (60-85°F). Avoid summer unless highly experienced, as heatstroke is a serious risk. Group travel with 4WD clubs is recommended for safety.

- Environmental Protection: Stay on designated roads to avoid damaging cryptobiotic soil crusts. Off-road driving is strictly prohibited. Pack out all trash and respect historical sites by leaving artifacts untouched.

- Navigation: GPS can be unreliable; carry a detailed topographic map (e.g., National Geographic Death Valley map) and a compass. Road signs are minimal, and junctions can be confusing.

History of Warm Springs Canyon and the Panamint Range

The Panamint Range, including Warm Springs Canyon, has a rich history tied to Native American habitation, mining booms, and modern preservation efforts. The Timbisha Shoshone, indigenous to Death Valley, used the region for seasonal hunting and gathering as early as 1000 CE, navigating the canyons for resources like mesquite and water sources like Warm Springs. Their presence persisted despite later Euro-American encroachment.

Mining activity surged in the 1870s during the California Gold Rush’s tail end. The Panamint Range became a hotspot after silver and gold discoveries in nearby Panamint City (1873-1876), though Warm Springs Canyon itself saw more activity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1880s, prospectors explored the canyon for gold, silver, and later talc, a soft mineral used in industrial applications. The Butte Valley Mining Company, incorporated in 1889, worked claims in nearby Goler Canyon and Warm Springs, targeting gold and silver veins yielding up to $20 per sack. Talc mining dominated by the 1930s, with operations like the Western Talc Company and Pfizer’s mines employing workers through World War II. Notable figures included Asa “Panamint Russ” Russell, who built the Geologist’s Cabin in Butte Valley in 1930 while prospecting gold, and Louise Grantham, who operated talc claims in the 1930s-1940s.

The early 20th century saw transient mining camps, with Warm Springs serving as a water source and rest stop for prospectors. The road itself evolved from wagon trails used by miners to access claims, later graded for vehicle use in the mid-20th century. By the 1960s, mining declined, and the area’s inclusion in Death Valley National Monument (established 1933, expanded to a national park in 1994) shifted focus to conservation. The Warm Springs Camp pools were constructed in the mid-20th century, possibly by miners or early park stewards, enhancing the site’s appeal for backcountry travelers.

Today, Warm Springs Canyon Road remains a testament to the region’s mining heritage, with relics like rusted machinery and stone cabins preserved under NPS oversight. Its remote beauty and historical significance make it a must-visit for those equipped to handle its challenges, offering a window into Death Valley’s rugged past and pristine present.