William Franklin Keys (September 27, 1879–1969) was a rugged American frontiersman, rancher, and miner who became a notable figure in the history of the Mojave Desert, particularly in what is now Joshua Tree National Park, California.

Early Life and Background

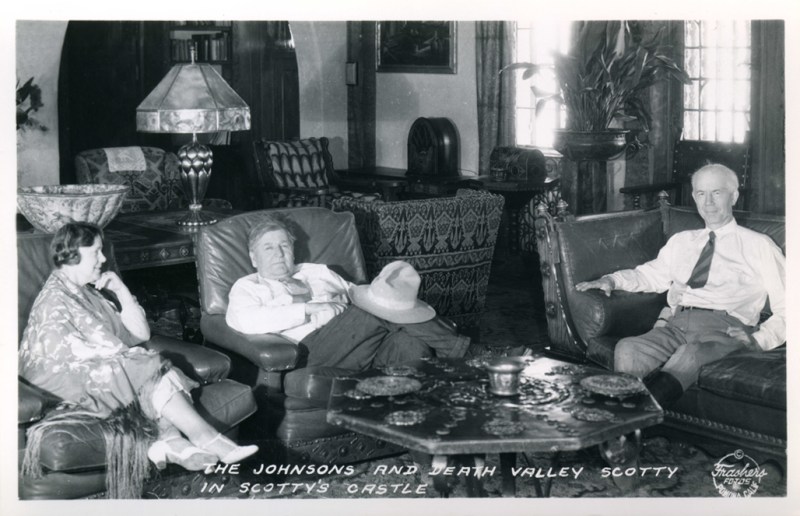

William Franklin Keys was born on September 27, 1879, in Palisade, Nebraska, to parents of Russian descent. In the early 1890s, his family relocated to Nebraska, where a young Bill began his journey into a rugged, self-reliant life. At age 15, he left home to work as a ranch hand, smelter worker, and miner, honing skills that would define his later years. His early adventures took him to Arizona, where he served as a deputy sheriff in Mohave County, and to Death Valley, where he befriended the colorful prospector Walter “Death Valley Scotty” Scott. Their association led to involvement in the infamous “Battle of Wingate Pass,” a swindle that added to Keys’ reputation as a tough frontiersman. By 1910, Keys arrived in the Twentynine Palms area of California, drawn to the harsh yet promising Mojave Desert.

Life in the Mojave Desert

In 1910, Keys took a job as custodian and assayer at the Desert Queen Mine in what is now Joshua Tree National Park. When the mine’s owner died, Keys was granted ownership of the mine as payment for back wages. In 1917, he filed for an 80-acre homestead under the Homestead Act, establishing the Desert Queen Ranch. He married Frances May Lawton in 1918, and together they raised seven children, three of whom tragically died in childhood and were buried on the ranch. The couple built a self-sufficient life, constructing a ranch house, schoolhouse, store, sheds, a stamp mill, an orchard, and irrigation systems, including a cement dam and windmill. Keys supplemented ranching with mining, operating a stamp mill to process ore for other miners and digging for gold and gypsum. His resourcefulness made the Desert Queen Ranch a symbol of early desert settlement.

The Wall Street Mill Dispute and Shootout

On May 11, 1943, a long-simmering feud with neighbor Worth Bagley, a former Los Angeles deputy sheriff, culminated in a fatal confrontation near the Wall Street Mill in what is now Joshua Tree National Park. The dispute centered on a property line and Keys’ use of a road that crossed Bagley’s land. Bagley, resentful of Keys’ access to the road for hauling ore to his mill, had posted a threatening sign: “KEYS, THIS IS MY LAST WARNING. STAY OFF MY PROPERTY.” On that fateful day, Keys, aware of the serious nature of such threats in the untamed desert, stopped his car to assess the situation. According to Keys, Bagley ambushed him, firing first. In self-defense, Keys returned fire, fatally shooting Bagley. Hours later, Keys turned himself in to authorities in Twentynine Palms, claiming he acted to protect his life.

Trial and Imprisonment

Keys was charged with murder and faced a contentious trial. The desert community was divided, with some viewing Keys as a hardworking homesteader defending his rights, while others saw him as an aggressor in a property dispute. The court convicted him, and he was sentenced to ten years at San Quentin Prison. During his incarceration, Keys utilized the prison library to educate himself, maintaining his sharp mind, which had been honed by years of navigating the desert’s challenges. His time in prison was marked by resilience, as he adapted to confinement with the same determination that had sustained him in the harsh Mojave.

Exoneration and Later Life

Keys’ conviction sparked controversy, and his wife, Frances, sought help from Erle Stanley Gardner, the renowned author of the Perry Mason novels and a frequent visitor to Joshua Tree. Gardner, moved by Keys’ story and convinced of his innocence, took up the case through his “Court of Last Resort,” a project dedicated to overturning wrongful convictions. Gardner’s investigation highlighted inconsistencies in the trial and supported Keys’ self-defense claim. In 1950, Keys was paroled, and in 1956, he received a full pardon, largely due to Gardner’s efforts. After his release, Keys returned to the Desert Queen Ranch, where he lived quietly until his death in 1969. To mark the site of the 1943 shootout, Keys placed a stone inscribed, “Here is where Worth Bagley bit the dust at the hand of W.F. Keys, May 11, 1943.” The original stone, vandalized in 2014, is now preserved in the Joshua Tree National Park museum, with a metal replica at the site.

Legacy

Bill Keys’ life embodies the tenacity and resourcefulness of early desert settlers. His Desert Queen Ranch, now part of Joshua Tree National Park, is preserved as a historic site, with park rangers offering guided tours from October to May to share his story. The ranch, with its array of buildings and mining equipment, stands as a testament to Keys’ ability to thrive in an unforgiving environment. The 1943 shootout, while a tragic chapter, underscores the challenges of frontier life, where disputes over land and resources could escalate to deadly confrontations. Keys’ exoneration, facilitated by Erle Stanley Gardner, highlights his enduring fight for justice. Today, the dirt road where the shootout occurred is a tourist attraction, and Keys’ story remains a compelling part of the Mojave Desert’s history.

Articles Related to Bill Keys

Albert Mussey Johnson – Death Valley Ranch OwnerAlbert Mussey Johnson Albert Mussey Johnson (1872 - 1948) was a businessman and investor who received notoriety as the millionaire, who built “Scotty's Castle” in… |

Bill Keys Gunfight – May 11, 1943In the desolate expanse of California's Mojave Desert, a violent clash unfolded on May 11, 1943, that would echo through the history of Joshua Tree… |

![The Battle of Wingate pass as reports by Los Angeles herald (Los Angeles [Calif.]), March 21, 1906](https://i0.wp.com/www.destination4x4.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/WinGatePass.png?fit=300%2C227&ssl=1) The Battle of Wingate Pass – February 26, 1906The Battle of Wingate pass as reports by Los Angeles herald (Los Angeles [Calif.]), March 21, 1906 The so-called "Battle" of Wingate Pass, which occurred… |

Walter Edward Perry Scott – “Death Valley Scotty”Walter Edward Perry Scott (September 20, 1872 – January 5, 1954), also known as "Death Valley Scotty", was a miner, prospector and conman who operated… |

Warner Elmore ScottWarner Elmore Scott (1865–1950) was a Kentucky native from a horse farming family who became entangled in his brother Walter "Death Valley Scotty" Scott's infamous… |