Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins was a member of the Paiute tribe and a Native American writer, activist, lecturer, teacher, and school organizer in the Humboldt County area of Nevada.

Early Life and Cultural Roots

Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins, born around 1844 near Humboldt Sink, Nevada, was a Northern Paiute woman whose Paiute name, Thocmetony, meaning “Shell Flower,” reflected her connection to her people’s traditions. The daughter of Chief Winnemucca (Poito), a Shoshone who had joined the Paiute through marriage, and Tuboitonie, she was the granddaughter of Chief Truckee, a prominent leader who advocated peaceful coexistence with Anglo-American settlers. Raised in the Kuyuidika-a band near Pyramid Lake, Sarah grew up in a world of dramatic change as white settlers encroached on Paiute lands following the 1848 California Gold Rush. Her early years were marked by the Paiute’s nomadic lifestyle, gathering plants and fishing, but also by fear of the “white-eyed” settlers, whom she initially believed might harm her people.

At age six, Sarah accompanied her grandfather Truckee to California, where she encountered unfamiliar Euro-American customs—beds, chairs, and bright dishes— sparking both curiosity and apprehension. By 1857, at Truckee’s insistence, she and her sister Elma lived with Major William Ormsby’s family in Carson City, learning English and adopting the name Sarah. In 1860, at 16, she briefly attended a Catholic convent school in San Jose, California, but was forced to leave after three weeks due to objections from white parents. Despite this, Sarah became fluent in English, Spanish, and several Native languages, skills that would define her role as a mediator between cultures.

Advocacy and Role in Conflict

Sarah’s life was shaped by the escalating tensions between the Paiute and settlers. The 1860 Paiute War, sparked by settler encroachment, claimed lives, including family members, and deepened her resolve to act as a peacemaker. In 1871, at age 27, she began working as an interpreter for the Bureau of Indian Affairs at Fort McDermitt, Nevada, leveraging her linguistic abilities to bridge communication gaps. Her 1870 letter to the superintendent of Indian Affairs, published in Harper’s magazine, marked her emergence as a public advocate, exposing the Paiute’s plight and gaining both attention and criticism.

During the 1878 Bannock War, Sarah’s role was both heroic and controversial. Learning that her father and other Paiutes were held hostage by Bannock warriors, she undertook a grueling 233-mile horseback ride to Pyramid Lake to warn her family and dissuade them from joining the conflict. She then volunteered as an interpreter and scout for the U.S. Army, freeing her father and others. However, her collaboration with the military led some Paiutes to view her as a traitor, a perception compounded by her advocacy for assimilation to ensure her people’s survival. After the war, the Paiute were forcibly relocated to the Yakama Reservation in Washington Territory, a harsh 350-mile winter march that devastated the community. Sarah, devastated by broken promises she had made to her people, worked as an interpreter at Yakama and began lobbying for their return to Nevada.

Literary and Public Advocacy

In 1880, Sarah traveled to Washington, D.C., meeting President Rutherford B. Hayes and Interior Secretary Carl Schurz to demand the Paiutes’ release from Yakama and their return to the Malheur Reservation. Despite promises, these commitments were never fulfilled, fueling her determination to reach broader audiences. From 1883 to 1884, she delivered over 300 lectures across the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, often billed as the “Paiute Princess,” a trope she strategically embraced to captivate white audiences. Her speeches, blending eloquence, humor, and sharp critiques of U.S. policies, challenged stereotypes and exposed the hypocrisy of Indian agents and the reservation system. She met luminaries like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Oliver Wendell Holmes, earning praise for her “eloquent, pathetic, tragical” oratory.

In 1883, with support from Elizabeth Palmer Peabody and Mary Peabody Mann, Sarah published Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims, the first autobiography by a Native American woman and the first Native woman to secure a copyright. The book, a blend of memoir and ethnohistory, chronicled the Paiute’s first 40 years of contact with settlers, detailing injustices like land theft, starvation, and broken treaties. Written in English—a language not her own—and at a time when women, especially Native women, lacked political voice, it was a groundbreaking achievement. The book remains a vital historical source, praised for its vivid imagery and unflinching critique of Anglo-American expansion.

Educational Efforts and Personal Life

In 1884, using royalties from her book and donations, Sarah founded the Peabody Institute near Lovelock, Nevada, a school for Native children that emphasized Paiute language and culture alongside English education. Innovative for its time, the school aimed to empower Native youth without forcing assimilation. However, financial struggles and lack of federal support forced its closure by 1887.

Sarah’s personal life was marked by complexity. She married three times: first to an unnamed Native husband (details unknown), then briefly to Lt. Edward Bartlett in 1872, and finally to Lt. Lewis H. Hopkins in 1881, an Indian Department employee who supported her work but struggled with gambling and tuberculosis. Hopkins died in 1887, leaving Sarah financially strained. Rumors of a possible poisoning by a romantic rival at her death persist but remain unconfirmed.

Later Years and Legacy

After her husband’s death, Sarah’s health declined. She moved to Montana to live with her sister Elma, where she died of tuberculosis on October 16, 1891, at age 47. Feeling she had failed her people due to unfulfilled government promises, Sarah nonetheless left an indelible mark. Her tireless advocacy—over 400 speeches, petitions, and her autobiography—brought national attention to Native injustices.

Posthumously, Sarah’s legacy has grown. In 1993, she was inducted into the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame, and in 1994, the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. In 2005, a statue by Benjamin Victor was placed in the U.S. Capitol’s National Statuary Hall, honoring her contributions. Sarah Winnemucca Elementary School in Washoe County bears her name, and her book continues to be studied as a foundational text in Native American literature. Despite criticism from some Paiutes for her assimilationist stance and military collaboration, she is celebrated as a trailblazer who navigated two worlds to fight for her people’s survival and dignity.

Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins remains a powerful symbol of resilience, using her voice to challenge a nation to live up to its ideals. Her life, as she wrote, was a fight for her “down-trodden race,” a mission that resonates in the ongoing struggle for Indigenous rights.

Nevada State Historical Marker

Nevada State Historical Markers identify significant places of interest in Nevada’s history. The Nevada State Legislature started the program in 1967 to bring the state’s heritage to the public’s attention with on-site markers. These roadside markers bring attention to the places, people, and events that make up Nevada’s heritage. They are as diverse as the counties they are located within and range from the typical mining boom and bust town to the largest and most accessible petroglyph sites in Northern Nevada Budget cuts to the program caused the program to become dormant in 2009. Many of the markers are lost or damaged.

Sarah Winnemucca, whose Paiute name was Thocmentony (Shell-flower), was the daughter of Chief Winnemucca, and granddaughter of Captain Truckee, a friend and supporter of Captain John C. Frémont. Sarah Winnemucca sought understanding between her people and European Americans when the latter settled on Paiute homelands. Sarah lectured, wrote a foundational book in American Indian literature, and founded the non-government Peabody School for Native children outside of Lovelock, Nevada. She worked tirelessly to remedy injustice for her people and to advocate peace. Here at Fort McDermitt she served as an interpreter and teacher. Because of her importance to the nation’s history, Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins was honored in 2005 with a statue in the National Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol.

STATE HISTORIC MARKER No. 143

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE

MRS. CURTIS S. HARNER

Nevada State Historical Marker Summary

| Name | Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins |

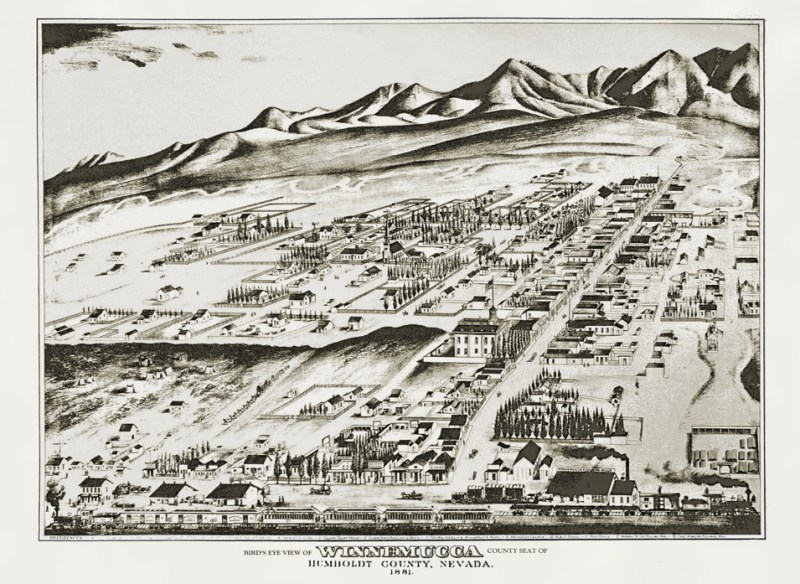

| Location | Humboldt County, Nevada |

| Nevada State Historica Marker Number | 143 |

| Latitude, Longitude | 41.9725, -117.6219 |