The Pioneer Memorial Park is Nevada Centennial Marker No. 2, installed in 1964 as part of Nevada’s celebration of its 100th anniversary of statehood and the beginning of the Nevada Historical Marker Program. The Marker is a monument for the men and women buried at the location and some of the earliest settlers of Nevada starting in 1863.

Nevada State Historical Markers identify significant places of interest in Nevada’s history. The Nevada State Legislature started the program in 1967 to bring the state’s heritage to the public’s attention with on-site markers. These roadside markers bring attention to the places, people, and events that make up Nevada’s heritage. They are as diverse as the counties they are located within and range from the typical mining boom and bust town to the largest and most accessible petroglyph sites in Northern Nevada Budget cuts to the program caused the program to become dormant in 2009. Many of the markers are lost or damaged.

Nevada State Historic Marker 2 Text

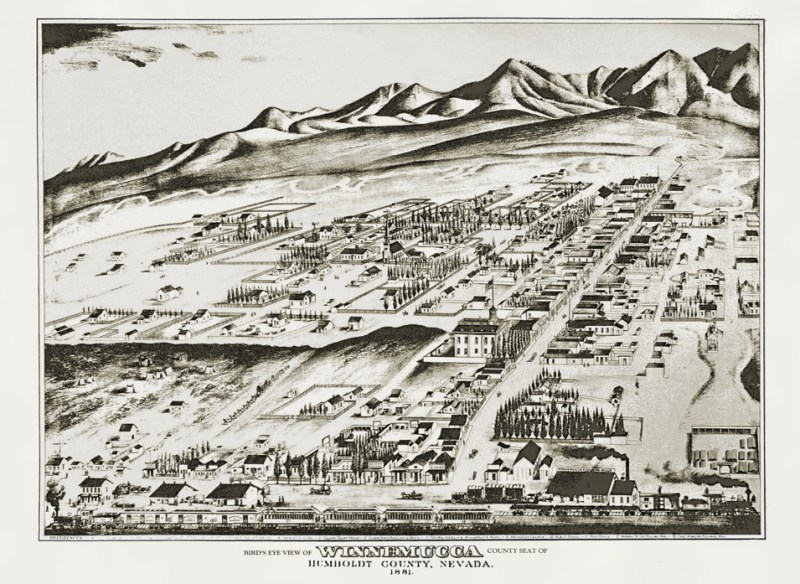

This part of the Pioneer Cemetery includes the last resting place of Frank Baud and other of the pioneers who founded Winnemucca, earlier known as French Ford. Baud arrived in 1863 and is one of the men credited with naming the town Winnemucca after the famous Northern Paiute chieftain.

Baud came with Louis Lay from California to work on the Humboldt canal, a project headed by Dr. A. Gintz and Joseph Ginaca who devised the plan to link Golconda and Mill City by means of a 90-mile canal and provide water for the mills in the area. It was never completed. Baud later became a merchant, helped build the Winnemucca Hotel with Louis and Theophile Lay, was the first postmaster, and gave the town a schoolhouse before his death in 1868.

CENTENNIAL MARKER No. 2

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE

Nevada State Historic Marker 2 Trail Map

Nevada State Historic Marker 2 Summary

| Name | Pioneer Memorial Park |

| Location | Pioneer Memorial Park, Winnemucca Humboldt County, Nevada |

| Latitude, Longitude | 40.9787, -117.7419 |

| Nevada State Historic Marker | 2 |